By Dessi Gomez South Bend Tribune

Artist Tuck Langland discovered his true calling on a date while an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota.

“We went to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts,” the St. Paul, Minn., native says. “And she’s telling me all about the art. I didn’t know anything about it.”

Prior to that date, Langland had had very little exposure to any type of art, except for music — he’s been a choir and operatic singer since attending a military high school where the headmaster, he learned later, didn’t “believe in fads and frills like the arts.”

The semester after that date at the museum, he enrolled in the art appreciation course his date had taken and eventually enrolled in a sculpture class as a junior.

“I signed up for a sculpture class, not really knowing what quite to expect,” he says. “I thought it was easy.”

And like that, Langland realized he had found his calling.

“It’s absolutely safe to say that I walked outta that class the very first day and I did not say to myself, ‘Gee, I like sculpture.’ I did not say to myself, ‘You know, I think I might go into sculpture.’ I said to myself, ‘I am a sculptor,’” he says. “It was a matter of finally discovering the thing that lay dormant in me all those years.”

Sixty years later, Midwest Museum of American Art executive director and curator Brian Byrn says Langland has been a significant “contributor to the cultural landscape” of the Midwest — and he’s assembled the collection to prove it.

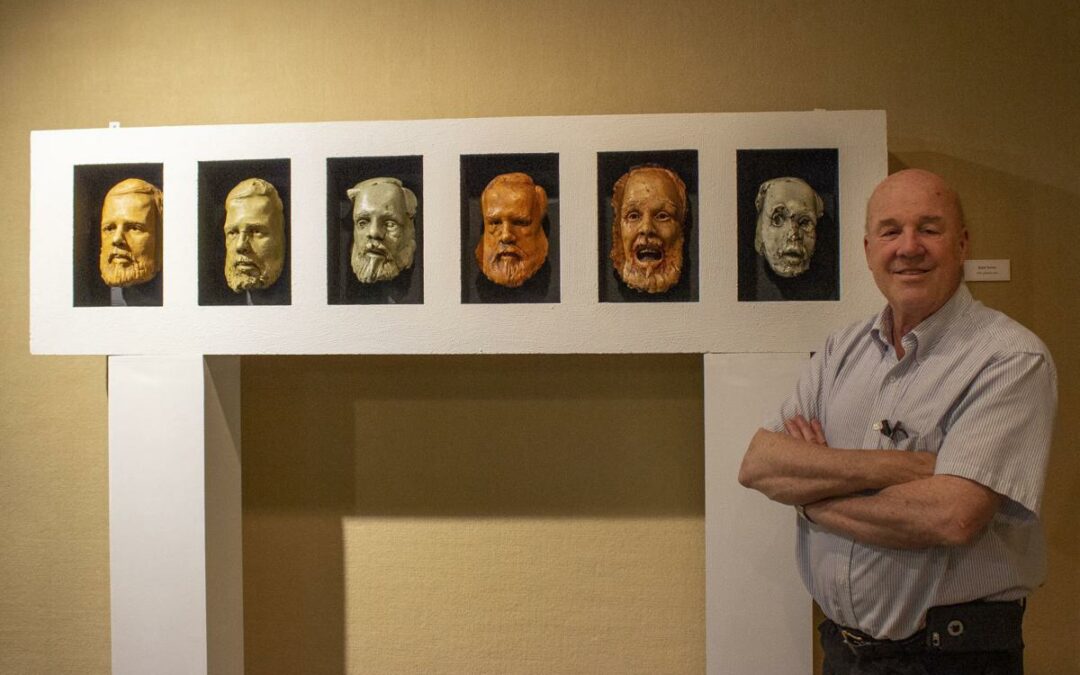

Byrn has collected 60 works by Langland over nine years. Right now, they form the exhibit “The Tuck Langland Collection: A Biography in Sculpture” that continues through July 28, but, eventually, they’ll be available to students and scholars for study even when not on public display.

“I didn’t want just all finished works,” he says. “I wanted to show something about the process.”

The collection includes works in all stages, from unrealized proposals to plaster or wax models ready for molding to actual finished bronze sculptures.

“For a lot of artists, their careers just get evaporated,” Byrn says. “If an artist doesn’t take some control over their legacy, they can be forgotten.”

Byrn proposed the idea of a collection of Langland’s work about nine years ago. He realized at the time that “no institution had stepped up to create a collection.”

The collection aligns well with the timing of the museum’s 40th anniversary. That means four decades of life for the museum combined with six decades of work from Langland.

“I felt it was important to connect it to the history of our museum,” he says. “This is a look into the American story.”

A professor of sculpture at Indiana University South Bend from 1971 to 2003 and co-founder of Fire Arts Inc. in South Bend, Langland continues to work.

This past January, he visited Egypt and has created many works inspired by that trip. He and his wife, Janice, will have a show featuring newer works near his 80th birthday later this year at Fire Arts.

“He loves Egyptian art,” Byrn says. “He loves anything from any kind of Neolithic and ancient art or ancient antiquities. And some of that is reflected in this collection.”

Most of the sculptures in the museum’s gallery are figures — Langland’s specialty and the form that has earned him the most distinction and commissions during his career. The earliest piece featured is a limestone carving of a head that Langland made around 1960.

“The figure is the most constant image in the world of art,” Byrn says. “And most people respond to the human figure. … We have this human need to belong and connect. And figures in art are something that people immediately connect to.”

One of Langland’s seminal works is the Venus Natarani, a dancing figure with arms outstretched, inspired by the Indian god Shiva Nataraja, the king of the dance.

“The figure can really cut through,” Langland says. “I can walk out in my studio, particularly when I have a life-size figure going, there’s somebody standing there, or sitting there, and that’s kind of neat.”

As the collection expands into other galleries, Langland’s figures begin to take on more variety and completion. Several depict athletes such as swimmers or people of prominence, such as the famous rendering of the Revs. Theodore Hesburgh and Martin Luther King Jr. located in South Bend.

“They handed me a photograph, and you think, ‘OK, I’m just copying a photograph,’” Langland says. “But remember that photograph had 25% of the information in it that I needed — mainly the front half and top half. I couldn’t see the back, couldn’t see the bottom half, front or back. I had to invent all that and had to make it look right from just a flat photograph.”

One of Langland’s teachers once told him that art has to last only long enough to be photographed. But Langland disagrees because he thinks seeing a sculpture in person will have more effect on the viewer.

“These things will be around for a long time,” he says about his sculptures. “And I kinda like that idea. I like the idea that bronze will last.”

He does, however, compare the purpose of art to that of photography — that is, to preserve human history, which he believes artists owe to the future, just as past artists did for the present.

“If your house is burning and you had to grab something and run, what would you grab? TV? Hell, no, you can buy those. Couch? No. Family photo album. Pictures of your grandparents’ wedding. Stuff like that,” Langland says. “Art is a family photo album of the human race. That’s who we were. You can’t know who you are until you know who you were.”